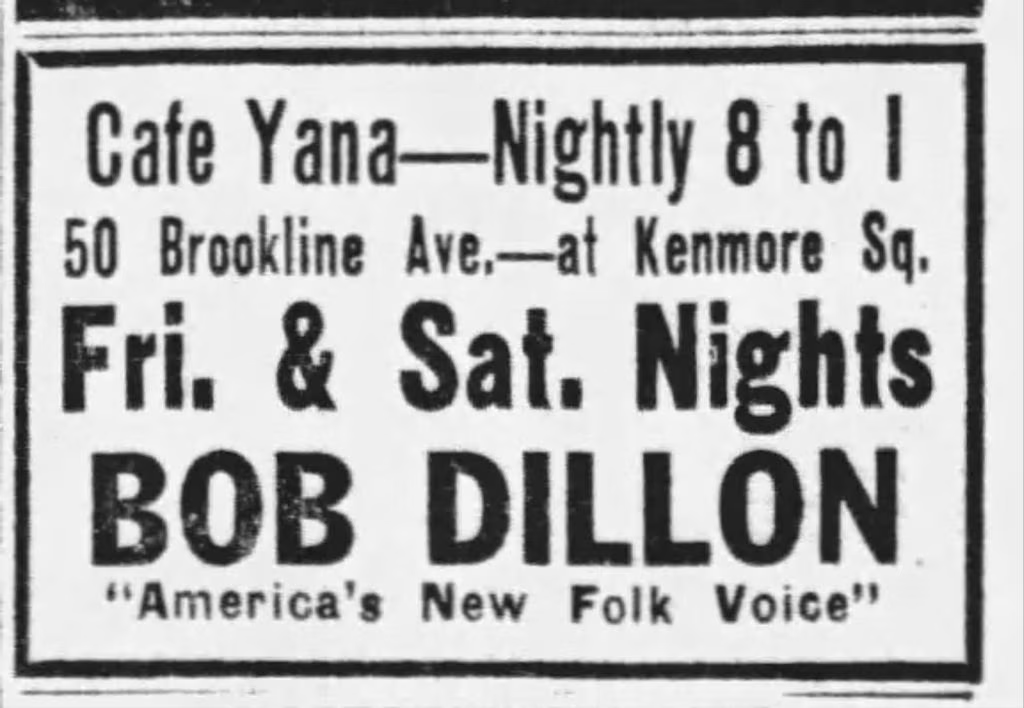

Sometimes there’s a very thin line between being a musical sensation and no one being certain exactly how you spell your stage name. If you were paying attention in April 1963 to newspaper ads for a pair of weekend shows at a Kenmore Square coffeehouse, you might not be certain if “Bob Dylan” or “Bob Dillon” was about to perform at Café Yana.

That spring 60 years ago, 21-year-old Bob Dylan was only just beginning to construct his monumental myth. His eponymous debut had been released 13 months earlier to a small, mostly warm reception, but he was far from being a household name. In the folk music circles of Greenwich Village and Harvard Square, however, he was an intoxicating curiosity who had manufactured his own rumors and origin stories until no one knew what was real and what wasn’t. His girlfriend, Suze Rotolo, for instance, had only recently learned his real last name — Zimmerman — when she spotted his draft card in their shared apartment.

Signed to Columbia Records and managed by Albert Grossman, Dylan was in the thick of recording his second album — “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan” — when he made his live debut in Boston. Its iconic cover image of Dylan and Rotolo walking down Jones Street in the West Village in the freezing cold dawn had already been snapped back in February. Released five weeks after the singer’s April weekend in Boston, “Freewheelin’” would introduce Dylan as a powerful songwriter to a rapidly expanding audience. It would completely capture the Beatles’ imaginations — they excitedly listened to the LP over and over — altering the way they’d approach songwriting, beginning with 1965′s “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away.” Within a year of the album’s release, Dylan would be back in Boston, this time selling out Symphony Hall.

Dylan had been to the city several times prior to that April 1963 weekend, but he had never enjoyed a proper venue booking. He had even been denied his own stage time at the it-folk venue, Club 47 on Mount Auburn Street in Cambridge — the scene rivalry between Greenwich Village and Harvard Square was very much real — and the singer-songwriter had only managed to appear before an audience there by convincing Carolyn Hester to bring him onstage during her set in August 1961. Without significant stage time to speak of, Dylan drank and swapped songswith New England folk musician Eric Von Schmidt at his apartment and, at one point, they found themselves in a backyard in West Roxbury, drunkenly trying to play croquet. “He was one of the most uncoordinated guys I’ve ever seen,” Von Schmidt told writer Anthony Scaduto. “He could just not make the mallet come in contact with the ball.”

The red-carpet-free Boston/Cambridge reception Dylan experienced in ‘61 was now transforming into a fevered, reverent welcome less than two years later. In the mimeographed pages of Broadside, Dave Wilson’s local biweekly folk music publication, a big reveal came a week before the Café Yana gig: “We couldn’t tell you his name then, but can now — Bobby Dylan. There is no other young performer today with as much magic surrounding his name. … As far as we know, this will be Bobby’s first Boston appearance — professionally at least.”

As for the club itself, it was nothing special, save for the music and people it attracted. Wilson recalls how dark it was inside Yana with its walls all painted black and its narrow corridor between tables and chairs leading to the small stage in back. Passing by it today — the coffeehouse at 50 Brookline Ave. occupied the rear portion of what is now the Cask ‘n Flagon — you certainly wouldn’t guess local music history was made there. Its capacity? Maybe 35 or 40 people.

On a small stage, stunning new music

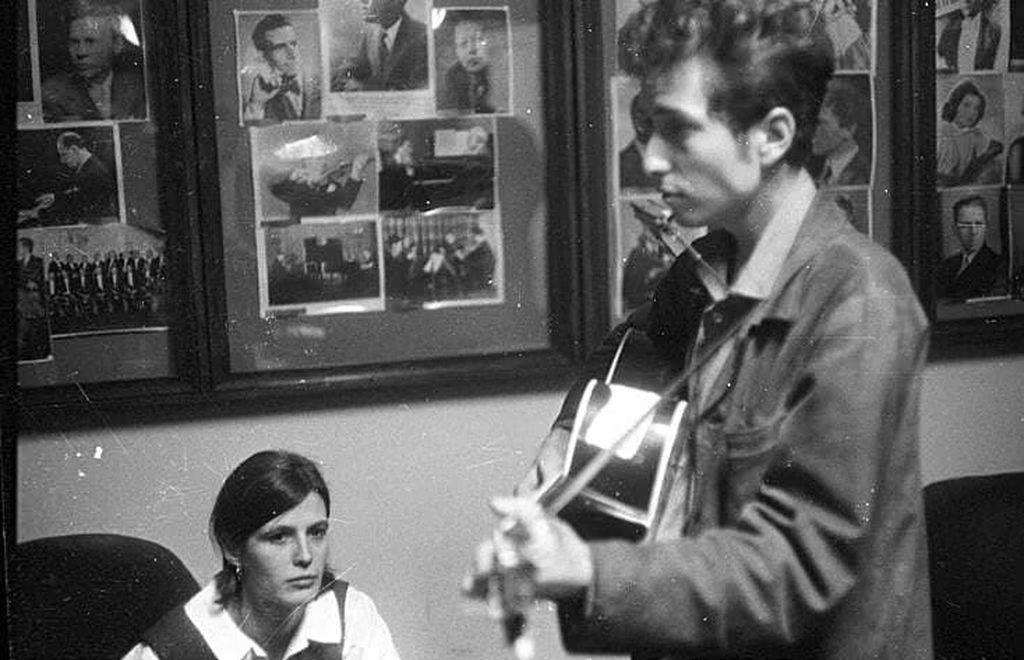

Café Yana waitress Susan Bluttman clearly remembers Dylan and Rotolo walking into the venue together that Friday evening on April 19, asking where they could hang out before showtime. Bluttman showed them to the loft above the kitchen in back and asked Dylan if he would play “Blowin’ in the Wind” during his set. His recording of the song was not out yet, but he had performed it on TV a year earlier; still, Dylan was shocked by her request. “He looked at me like, ‘Where the [expletive] did you hear that song?’” Bluttman says, “and I told him that Buffy Sainte-Marie covered it when she performed at Yana a few months prior.” Dylan would oblige her request.

This song request was not the only pre-concert surprise waiting for Dylan in Boston. Wilson regularly aired live performances from Café Yana on his “Coffee House Theatre” radio program on MIT’s WTBS-FM. Apparently, no one told Dylan that his performance would go out live, and he became nervous when Wilson quietly spoke to him about it right before his set. “I knew what he worried about,” Wilson says, “that Albert Grossman would chew his ass out if he found out he performed on the radio for free.” Wilson managed to convince Dylan that the station had a weak campus signal and that not many people would even hear it.

READ MORE: