Club 47

The Civil Rights Movement

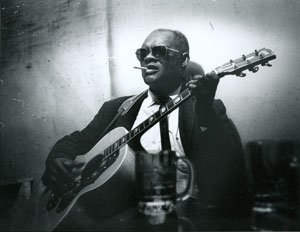

Harvard Square’s Club 47, later named Club Passim, was one of the first venues in a northern city to feature African American blues musicians from the South. Many of the blues greats such as Mississippi John Hurt and Reverend Gary Davis passed through Cambridge and found a welcoming home in a time when much of the country was hostile if not outright dangerous. Cambridge residents Dick Waterman, Ralph Rinzler, Jim Rooney, Joe Boyd, and others helped make this circuit possible, while people like Nancy Sweezy and Betsy Siggins gave blues musicians a place to stay when Cambridge hotels would not rent to African Americans.

As a part of the Centennial Celebration of the Harvard Square Business Association we are featuring brief portraits of Harvard Square businesses and their role in the history of Cambridge. Below are three photos and brief snapshots of some of the many blues musicians that performed at Club 47 and have been a part of Harvard Square’s history in the past 100 years. (The information in this article is from two interviews with Betsy Siggins of the New England Folk Music Archives, one on February 9, 2010 by Robin Lapidus and one on February 10, 2010 by Gavin W. Kleespies of the Cambridge Historical Society.)

Jackie Washington was a very popular performer at Club 47 for most of the time the club was open. He began playing there while he was a student at Emerson College and became a fixture of the folk music scene in Cambridge and Boston. He drew musical influences from the folk landscape that surrounded him as well as from his African American and Puerto Rican roots. He was one of the first people in the area to sing Hispanic folk music and became known as an extraordinary performer.

However, his time in the area also reflected the challenges faced by a person of color in the 1960s. Betsy Siggins, former staff member at Club 47, remembers one time he was arrested in Boston. He had been walking down Commonwealth Avenue when a police car stopped him. When he asked why he was being stopped, the police told him it was because he was “abroad in the night.” An altercation followed, and Jackie Washington ended up in jail. He later challenged the arrest in court and won, but it was a painful experience and a reminder for his friends in Club 47 of the real challenges faced on a daily basis by performers of color just outside the walls of the club.

Jackie Washington later signed with Vanguard Records, becoming one of their first artists of color.

Club 47 became an important stop in a circuit that brought some of the blues greats from the South and introduced them to audiences in northern cities. People like Dick Waterman became major conduits along this trail, working to make contacts and help to make the trip from the South to the northern cities one that was adventuresome rather than fearsome.

The arrival of musicians like Mississippi John Hurt and others that traveled this circuit opened the eyes of the club staff, folk fans, and other performers. It showed that there was an entire country out there, populated by real people with real stories, some of which were stories of real hard times. It showed that there was a lot more to this country than what was seen in Cambridge. For performers like Bob Dylan and Joan Baez the performances and stories of blues musicians like Mississippi John Hurt at Club 47 became a widow to a different perspective on the whole country.

Betsy Siggins, former staff member at Club 47, remembers that meeting these performers and hearing their stories of a different kind of an American life in the left an impression that hasn’t wavered since.

When the first African American blues performers began performing at Club 47, there wasn’t a hotel in Harvard Square that would allow a black man to stay. Many of the performers would stay with staff members from the club. Betsy Siggins remembers the experience of having blues greats like Reverend Gary Davis stay on her couch. When people heard he was in town, Siggins would find 20 people had gathered at her home to hear him play and to tell his stories. Everyone knew that they were a part of something that had not yet been discovered.

Betsy also remembers that Davis, a blind man, had one suit, one coat and one hat and that most of the time he was wearing them. In a habit grown from fear, he slept with everything he owned on his body.

Photo Credit: Dick Waterman

Music in Harvard Square

Music is an undeniable part of the history and allure of Harvard Square. The storied list of performers in jazz clubs, blues houses, coffee shops, movie theater lobbies, and on the streets is staggering. Some of the biggest names in American music of the last half-century got their start as unknowns in Harvard Square. Below, we will look at four of the spaces that have made Harvard Square a famous music venue, Club 47 or Passim, The Nameless Coffeehouse, The House of Blues, and the streets of The Square.

No one could foresee the 47 Mount Auburn Jazz Coffee House changing the face of American music when it was first founded in 1958 by Paula Kelly and Joyce Kalina. Initially unwelcomed by their neighbors in Harvard Square, the 47 had to become a nonprofit, charging people $1 to be “members” in order to stay in business—thereby adding “club” to create the name Club 47.

The folk revival movement of the 1960s forever changed American music, and that change manifested itself solidly in Club 47.

One Tuesday night performer was listed as the anonymous “Girl with Guitar.” That performer turned out to be Joan Baez. Soon after Club 47 opened, at age 17, Baez gave her first performance. Thrust into the music scene that was forming around Club 47, Baez soon connected with Debbie Green and Margie Gibbons. The girls wrote music together, taught each other songs, and dated other young singers and guitar-players from Harvard. Their sounds mixed, blended, and evolved, and a musical revolution began to take shape centered on Club 47.

For the next ten years, hundreds of performers would make the pilgrimage to Club 47 to be part of the Cambridge folk music world: The Charles River Boys, Jim Kweskin, Jim Rooney, Eric von Schmidt, Joni Mitchell, Judy Collins, Pete Seeger, Clay Jackson, Ethan Signer and Taj Mahal. Many were students, or drop-outs, from Harvard, BU, and Radcliffe, such as Tom Rush and Bonnie Raitt. Joan Baez knew a good, young singer whom she brought to Cambridge, but Club 47 was booked. Bob Dylan, therefore, played for free between sets, never playing an official gig.

By the late 1960s bands had begun to replace the solo acts from the earlier years, and other changes did not bode well for the club. The original owners left to pursue other careers, and the location of Club 47 moved to Palmer Street, though a successful petition readdressed the site from #29 to #47 kept part of the address the same. Things only got worse, however, and in 1968 the club closed. A year later the concept was reborn under the name Passim, which itself became a nonprofit, and later Club Passim.

In its reincarnated form, Club 47 lives on through Club Passim which has grown to include a music school and a cultural exchange program for kids. For its 40th anniversary, the club celebrated at Sanders Theater and some of the artists who got their start at the club played a benefit concert which included Tom Paxton, Muddy Waters, Taj Mahal, Suzanne Vega, Tracy Chapman, Shawn Colvin, and Joan Baez. Club 47 is certainly not the only music house that played an important role in the music culture of Harvard Square both past and present. Many of the artists who performed at Club 47 also played at The Nameless Coffeehouse. Proudly proclaiming their role as “New England’s oldest all-volunteer coffeehouse- forty-four years of bringing great folk music to Harvard Square!,” The Nameless Coffeehouse features entertainment ranging from folk and blues to bluegrass and comedy.

The Nameless is unique for it is entirely volunteer-run, and anyone, regardless of means, is welcome. It is volunteers who book acts, serve food, and set up for the bands, and audience members are asked to help clean up after performances. Perhaps slightly less well known than Club Passim, The Nameless views itself as a launching pad for artists and has hosted names such as Tracy Chapman, Patty Larkin, Ellis Paul, Dar Williams, John Gorka, Bob Franke, Ric Ocasek, and comedians Andy Kaufman and Jay Leno.

Although no longer in Harvard Square, there is one site that is not to be forgotten, or outdone by its larger and more glamorous branches: The House of Blues was founded in Harvard Square in 1992. With the intention of focusing on folk music from the Deep South, Hollywood and music icons invested in and opened the first of what would soon grow to be a highly successful chain of music venues. Dan Akyroyd, Aerosmith, George Wendt, Paul Schaffer, John Candy, River Phoenix, and Harvard University were among the first investors. The House of Blues now exists in 12 locations across the country, though the original location in Harvard Square closed in 2003. The origin of House of Blues serves to add to highlight the importance of the music culture of Harvard Square.

Harvard Square has been on the vanguard of American music since the late 1950s. One way that it has continued to remain relevant is with its the famous, if a bit motley, assortment of street performers. One that is perhaps the quintessential modern example of Harvard Square’s folk charm is Ratsy. Born in Michigan, Ratsy attended college, earned her cosmetology license, and then moved to Boston to become a singer. She sang underground in the subway for 3-4 years until her friend encouraged her to enter the now-defunct Acoustic Underground Competition, a national singer/songwriter competition in Boston, where she was named Best Female Performer. She has put out three CDs (The Subway Songstress Years (1992), Squished Under a Train (1995), and Flowery Swimsuit: The Live Album (2000)), and her first album was nominated for the Boston Music Awards.

Ratsy played The Nameless Coffeehouse and was a regular at Club Passim while touring the folk music scene in Boston. In fact, her final gig in Boston, before moving to California to pursue an acting career was at Club Passim. Since moving to the West Coast, Ratsy has appeared in several television commercials and an episode of the show Gilmore Girls.

Ratsy is just one, though certainly a dramatic example, of the continuation of the music culture of Harvard Square that was started at Club 47 and continued with both The Nameless Coffeehouse and The House of Blues. While some of the greatest artists of a generation got their start in Harvard Square more than 50 years ago, new and different artists continue to perform on the same stages that saw the birth of American musical icons.

As prepared by:

Gavin W. Kleespies, Executive Director Cambridge Historical Society.

Katie MacDonald, Intern Cambridge Historical Society.